DISCLAIMER: The information and views set out in this article are those of the author(s); and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Centre for Policy Studies or the Indian Institute of Technology Bombay.

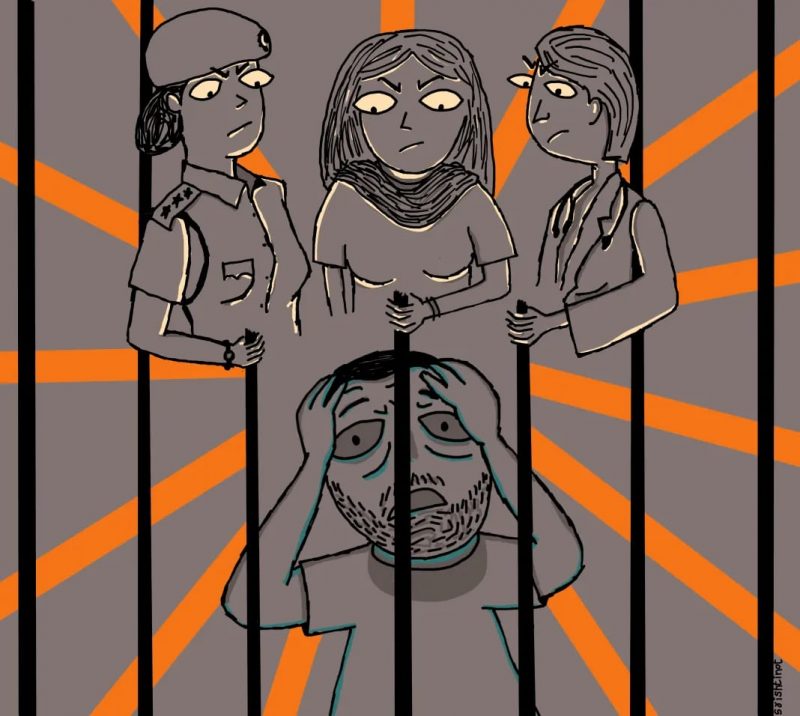

Amidst the chaos of a pandemic, when nothing seems more secure than house arrest, the Indian state seized the opportunity to put an end to a long standing trial – first of the accused and then of the collective conscience – with the execution of the four men convicted in the Nirbhaya rape case. But is this justice? Or merely the appearance of it?

The gruesome incident of rape occurred on the evening of 16 December, 2012; on what must have been a very long night for the victim Jyoti Singh, her family, the accused and the police. Thereafter the case was rigorously pursued and heard, across a fast-track court, the Delhi High Court and the Indian Supreme Court, between December 2012 and December 2019. Every appeal and every review led to a confirmation and re-confirmation of the death sentence imposed by the fast track court that had first heard the case. A total of four death warrants were issued in the case; and the death penalty that was first issued in September 2013 was finally carried out in March 2020 – after six long years. Jyoti Singh, unfortunately did not get a chance to witness either the judgement in the case or the people’s movement to improve women’s safety in public spaces that the incident stirred.

Public outrage at the incident, which soon turned into a social movement – revolving around the case and the judgment that was consequently passed – will remain a turning point in the women’s rights movement in India.

The Justice Verma Committee Report

Within a fortnight of the incident, a three member committee headed by Justice J.S. Verma, a former Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, was constituted to recommend amendments to the Criminal Code in order to enable quicker trials and enhanced punishments for criminals accused of committing sexual assault against women (Kalra 2013). The report that was submitted in January 2013 was exhaustive in its recommendations. It approached the issue of sexual assault towards women in a holistic manner, extending the responsibility of ensuring women’s physical safety to educational institutions and civil society organisations; along with suggestions for police reform and investigating procedures. While the recommendations of this committee were not adopted in their entirety (Dhar 2013), what did result from the exercise was an increased awareness about the possibilities (in terms of spaces and mechanisms) for improvement in ensuring women’s safety. Despite the delays in police investigation, court trial procedures, and the insensitivity within such procedures towards victims that continue to remain evident (Sebastian 1980, Partners for Law in Development 2017); my ethnographic fieldwork in police stations [1] reveals that in the routines of the everyday, any form of sexual assault against women is treated as a serious crime [2] that sets the machinery into action almost immediately. Whether it is due to the fear of being held accountable, or a genuine change in morale, gender sensitivity is performed at different levels in a police station, such as through the urgent recording of FIRs in issues of sexual assault, the refusal to record women’s statements in the absence of a female officer or constable, and the hesitation to bring female accused or suspects to the police station after sunset.

The Nirbhaya Fund

In the aftermath of this rape case, the Centre announced a separate fund of Rs. 10,000 crore to ensure the safety of women in India. Known as the Nirbhaya Fund, this resource enables state governments to receive money from the Centre, in order to be utilized for programmes meant to ensure women’s safety. The programmes initiated by state governments must be approved by the Ministry of Women and Child Development, which is the nodal agency for expenditure under this scheme. A simple google search however reveals that less than 20% of this fund has been utilized in the last eight years (Dutta 2019; Pandit 2019). The rehabilitation of victims of sexual assault, the lack of women constables in police stations, the threat to safety that women perceive in public spaces, the delays in procedure such as examination of forensic reports that the pursuit of court cases for sexual assault are fraught with, pose real and continued challenges, even for women who choose to display nirbhayta (courage).

Has Justice been Done?

The Nirbhaya case will remain a landmark in the Indian women’s rights movement because of the legislative developments that followed, such as fast track hearings of rape trials, the Verma Committee Report and the Nirbhaya Fund ; and not because the death penalty issued to the four persons convicted of rape was finally executed. What then is the significance of the execution of this death penalty? Amartya Sen points out in the Idea of Justice that justice should not only be done but it should be seen to have been done (Sen 2009, 392). When justice is seen to be done, what would have sufficed by being simply judicially sound also receives the validation of the collective conscience. A study by the Centre for Death Penalty at the National Law University in Delhi revealed that in justifying the death penalty, judges also tend to adopt the argument of collective conscience and public outcry (Kanga 2020). The carrying out of the death penalty did exactly this: it granted a seeming tangibility to the idea of justice being done. Justice has now “been seen” to have been done and therefore (as the applause on social media reveals) believed to have been done by society at large. For those in power, it might secure a vote bank; and on the global map, this death penalty may be perceived as India’s tribute, albeit symbolic, towards furthering the cause of women’s rights. But those who grapple with the strife of ensuring their own safety in public spaces every day, know that it is in factors such as the efficient use of the Nirbhaya Fund and adoption of the Verma Committee Report’s recommendations in their entirety, that justice will have been done in the Nirbhaya case. The hanging of the four convicts merely creates an illusion of this.

*****

Notes

[1] This information has been drawn on the basis of the author’s fieldwork on the everyday working of police stations in the city of Mumbai, for a post-doctoral research project.

[2] What is a “serious” crime is often decided and learned by police personnel through their experience. Murder, kidnapping and rape, I have been told, were always perceived as very ‘serious’ crimes. However, court orders and the public attention received by certain types of crimes also adds to importance given particular types of offences under the Indian Penal Code. Any form of sexual assault against women, crimes under section 498A (harassment for dowry) and online frauds have gained significance in police stations in this manner.

Bibliography

Dhar, Aarti. (2013, February 2). Verma Panel Recommendations Negated: CPI(M). Retrieved 22 March 2020, from The Hindu: https://www.thehindu.com/news/

Dutta, Prabhash. (2019, December 5). Nirbhaya Fund Utilisation Shows Why Women Continue to Be Unsafe in India. Retrieved 22 March 2020, from India Today: https://www.indiatoday.in/

Kalra, Harsimran. (2013). Report of the Committee on Amendments to Criminal Law, 2013. Retrieved 22 March 2020, from PRS Legislative Research: https://www.prsindia.org/

Kanga, Surabhi. (2020, January 31). We Villainise Rapists to Exonerate Ourselves: Anup Surendranath on the Futility of the Death Penalty. Retrieved 22 March 2020, from The Caravan: https://caravanmagazine.in/

Pandit, Ambika. (2019, December 8). Nearly 90% of Nirbhaya Fund Lying Unused: Govt Data. Retrieved 22 March 2020, from Times of India: https://timesofindia.

Sen, Amartya. (2009). The Idea of Justice. London, England: Allen Lane.

Image: Srishti Sharma/iStaunch