DISCLAIMER: The information and views set out in this article are those of the author(s); and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Centre for Policy Studies or the Indian Institute of Technology Bombay.

‘Instrumental Lives – an intimate biography of an Indian laboratory’ (Routledge, xxii+126, (HB), Rs 695, ISBN: 9780367856298). To buy this book, please write to psekhsaria@gmail.com.

Note: This is an excerpt from the book Instrumental Lives – An Intimate Biography of an Indian Laboratory (Routledge, 2019) by Pankaj Sekhsaria

Book Abstract

Instrumental Lives is an account of instrument making at the cutting edge of contemporary science and technology in a modern Indian scientific laboratory. For a period of roughly two-and-half decades, starting in the late 1980s, a research group headed by CV Dharmadhikari in the physics department at the Savitribai Phule University, Pune, fabricated a range of scanning tunnelling and scanning force microscopes including the earliest such microscopes made in the country. Not only were these instruments made entirely in-house, research done using them was published in the world’s leading peer reviewed journals, and students who made and trained on them went on to become top class scientists in premier institutions.

The book uses qualitative research methods such as open-ended interviews, historical analysis and laboratory ethnography that are standard in Science and Technology Studies (STS), to present the micro-details of this instrument making enterprise, the counter-intuitive methods employed, and the unexpected material, human and intellectual resources that were mobilised in the process. It locates scientific research and innovation within the social, political and cultural context of a laboratory’s physical location and asks important questions of the dominant narratives of innovation that remain fixated on quantitative metrics of publishing, patenting and generating commerce.

The book is a story as much of the lives of instruments and their deaths as it is of the instrumentalities that make those lives possible and allow them to live on, even if with a rather precarious existence.

Introduction to Extract

In this extract the author describes the process by which he gains access to the laboratory, that he then studies over a period of four years using tools and methods from history, sociology and anthropology. His first impressions are of a scattered and messy place that do not confirm to the common image of a lab as a structured and well organised space. This has implications in understanding the nature of scientific work in a laboratory and to a larger understanding of scientific and institutional processes.

EXTRACT from Chapter 1

Introduction: Entering the lab/setting the stage

1.2 Entering the labs

Later that afternoon Dharmadhikari took me briefly to his two (physically) small labs – one the scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) lab, the other his scanning force microscopy (SFM) lab. I met two of his latest doctoral students there, was shown a power point of some of the work that had been done in the labs over the years and also the images they had made with their instruments. The most striking of these for me was the nano-sized image of the syllable etched out in the Devanagiri script on a surface of gold. I found this image striking for two reasons – first, because it came across a bit like repeating the iconic 1990 image of IBM that had been spelt out with 35 individual xenon atoms (Baird, 2004; Eigler & Schweizer, 1990) and second (retrospectively), because of the significance that has as a religious symbol and in the stories of origin in Hindu religion and mythology.

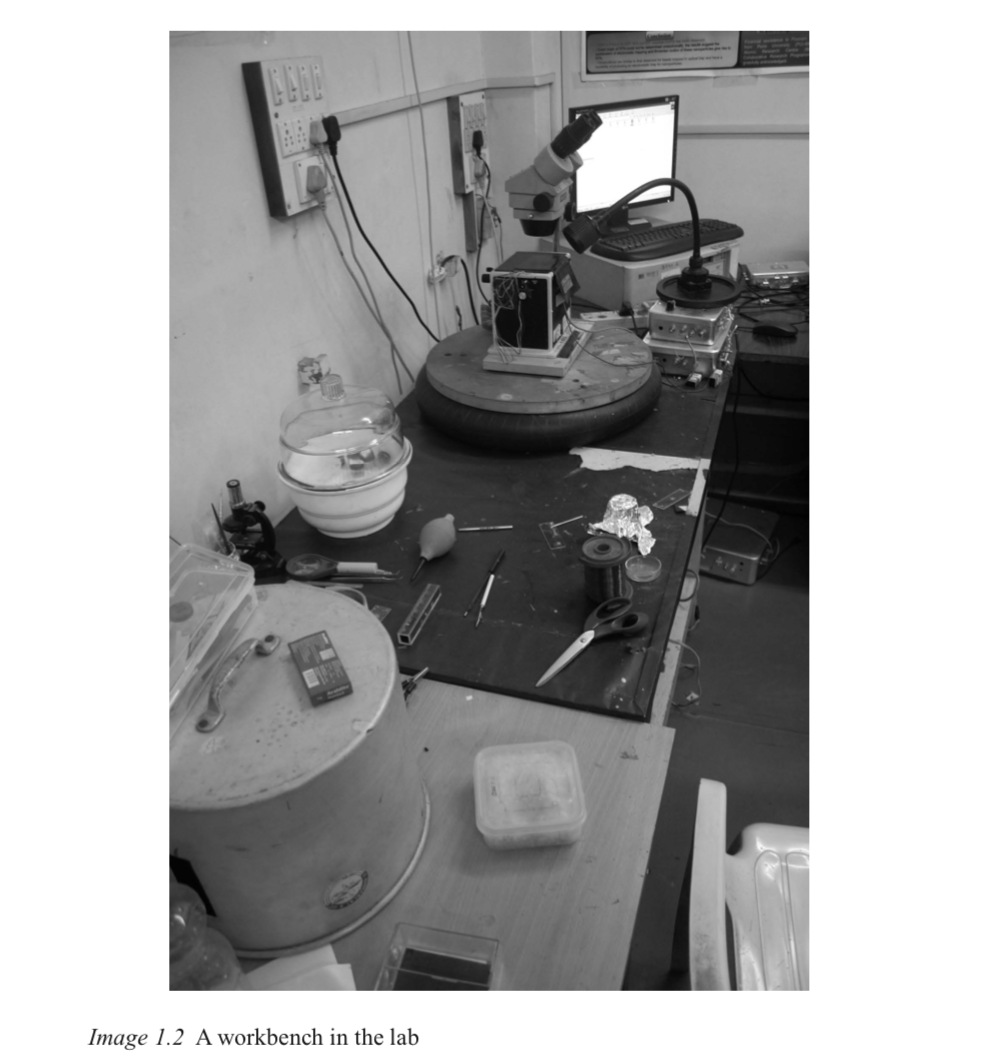

I experienced the labs themselves as hugely scattered clutter – small spaces that were crammed with chairs, computers, book shelves, cupboards and tables on which one saw a number of things: tools such as pliers, screw-drivers, nuts, bolts, small boxes of plastic and aluminium, double sided tape, glue sticks, scraps of paper, sheets of paper, files, books, pens, pencils, circuit boards, streams of wires running from here to there and, of course, a series of big and small instruments. In the corner of one lab was a refrigerator shell and a plywood box, each housing an STM that had been fabricated in this lab. In the other lab I saw a large upturned aluminium vessel of the kind we use to boil water on the gas stove in the kitchen at home. Underneath was a contraption that lay on the inflated tube of an automobile tyre – another STM, which too had been made in-house.

At first sight this set-up did not conform at all to my (and presumably also to many non-scientist’s) general idea of labs as clean, organised and disciplined spaces (Traweek, 1988). It was, in fact, the archetype and the material embodiment of disorder from which the scientific enterprise produces order and meaning (Latour & Woolgar, 1986; Traweek, 1988). I can say this with confidence now only on account of much retrospective insight, but, even then, a lot of it seemed counter-intuitive. It was in many ways the first indication that there was something here that went much deeper than was visible on the surface. There was a sense of excitement and anticipation of what my research would reveal and what the eventual story would be. But more than anything else, it was a sense of immediate relief I felt at that moment – I had managed to get access to the labs and my ‘work’ could finally begin!

1.3 The first set of insights

The short, 30-minute interview that I conducted with Dharmadhikari and the brief tour of the labs that first day, laid out very broadly and in an unstructured manner, the history, trajectory and chronology of Dharmadhikari’s scientific journey that included the indigenous and in-house creation of among the earliest, if not the first STMs and atomic force microscopes (AFMs) in India. This was a journey that started somewhere in the mid-1980s (though one can pull it back further into time) and to which my doctoral research became an unexpected and unplanned add-on rather quickly. It helped that Dharmadhikari was himself intrigued about what I was doing – just the fact that someone was interested in the history of his scientific endeavours and also that something like STS existed at all.

Somewhere towards the end of that first day Dharmadhikari told me that under normal circumstances he would not have given the time he had given me. He had decided to make an exception following our phone conversation, he explained, because he had sensed excitement and was interested in the subject himself. Looking back retrospectively, the decision he made that day to give me access and also his time over the next many months had a much larger significance than I had initially assumed. It is conjecture on my part today, but these were already written into the subtext of that specific context and what unfolded because Dharmadhikari had retired just a few days before I first met him. I had thought then that it was a great time for me to get into the picture – the story I would tell would be like the perfect closing of the loop – an interesting journey in a modern physics laboratory now coming to its logical end with the professor retiring after many decades of work. As I was to realise in the months that followed, however, this perfect loop was only the creation of my own imagination. There was/is no perfect loop, and there surely is no perfect closure. The point I entered may have seemed like the closure of something, but it was also the entry point for something else – something like one funnel opening into another – the first one moving towards closure but actually opening out into another huge world that could funnel into unknown directions.

My research was not structured in any particular manner. It moved unexpectedly like any research does – sometimes smooth and fast, sometimes stagnant, sometimes turbulent eddies; not threatening in any way, but eddies nevertheless. There were a number of things I did as a researcher and an ethnographer in the four-year period I engaged with these labs.

There were the long winding interviews – some conducted in the lab with Dharmadikari and his current students, one with Dharmadhikari’s wife at their home and others with former students, collaborators and former col- leagues in their respective homes or current work places. I managed to sit in for the PhD defence of one of Dharmadhikari’s students in the university and took copious notes of what transpired. I attended Dharmadhikari’s farewell seminar organised in the department and, when the opportunity allowed, other nanoscience and technology-related seminars, workshops and conferences around the country.

I also spent a lot of time in the labs – one part of it chatting with the researchers as they went about their work, another rummaging through the racks and cupboards full of paper – this included Master’s, MPhil and PhD theses; notebooks crammed with scribbled notes; one set of files full of scientific papers; another set with invoices, bills and receipts and a third that had correspondence of various kinds. Some of the best time I personally had was when I was photographing the labs – how does one meet the eternal challenge of visually capturing and conveying the essence of the space and the subject of the photograph? I photographed the lab spaces, the researchers as they worked, the instruments that were under construction and also those that already sat on the workbenches. A big sense of joint achievement was when one of these photographs made it to the cover of the May 2013 issue of Current Science, India’s leading scientific journal. And then there was also the more relaxed, winding-down time, chatting, sipping chai and munching glucose biscuits in the canteen I had first met Dharmadhikari.

The account that you will read in the following pages is the outcome, via all the above, at documenting and structuring the journey of the laboratory from my window and from within the framework of Science and Technology Studies (STS) that was as new to my subjects as the STM was to me when I first heard about it. At the heart of this multidimensional exercise was an attempt to answer three main questions, each an independent one in itself but also inextricably linked to the other:

(a) What actually happened in Dharmadhikari’s lab? What did Dharmadhikari actually do?

(b) What can/does this story tell us about scientific research and innovation in India? and

(c) How does one locate this work within the larger narratives and discourses of innovation in the Indian context, but also globally?

And all of this, of course, was subservient to my larger doctoral research project, which spanned six years and five nanoscience and technology labs in three cities of India. Dharmadhikari’s labs were a crucial component of my journey and it is only befitting that this book should be about their story and their journey.

References:

Baird, Davis. (2004). Navigating Nano through Society. University of South Carolina.

Eigler, D. M. & Schweizer, E. K. (1990, April 5). Positioning single atoms with a scanning tunnelling microscope. Nature 344, 524–526 (1990) doi:10.1038/344524a0

Latour B. & Woolgar S (1986). Laboratory Life: The Social Construction of Scientific Facts. New Jersey, USA: Princeton University Press.

Traweek, Sharon. (1988). Beamtimes and Lifetimes: The World of High Energy Physicists. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Images: Pankaj Sekhsaria