DISCLAIMER: The information and views set out in this article are those of the author(s); and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the Centre for Policy Studies or the Indian Institute of Technology Bombay.

Introduction

On April 12, following petitions filed by the Election Commission (EC) and the Association for Democratic Reforms challenging the use of electoral bonds, the Supreme Court directed political parties to submit information on the funds received through bonds to the EC, by May 30 (Rajagopal 2019). This is an interim order; the Supreme Court is still to decide on the constitutional validity of electoral bonds. Why has this matter come before the Court?

Political parties need large amounts of money to function. Individuals, firms, and companies can donate money to political parties of their choice. This process has long been marred by corruption and opacity (The Wire 2018; Chishti 2018). Additionally, these donations have been a hotbed for money laundering and quid pro quo deals that citizens are not privy to (The Wire 2018). This dilutes the veracity of the electoral process and adversely impacts democracy.

Attempts have been made to ensure that donations to political parties are more transparent and less amenable to corruption. Electoral trusts, tax breaks for donors, and the rule to declare sources when cash donations exceed a certain amount are some examples. However, these policies are riddled with loopholes and inconsistencies (Meghnad S. 2017; Stevens and Sethi 2017).

Electoral bonds, introduced by Finance Minister Arun Jaitley in his 2017 Budget Speech, are purportedly another effort to make the electoral funding process more transparent, thereby making elections more free and fair—an indispensable element of any democracy. The government notified the scheme on 02 January 2018 – amending the RBI Act, the Representation of the People Act, and the Companies Act – and the first bonds were made available in March 2018.

Electoral bonds and transparency in the electoral process

As per the 02 January 2018 notification (GoI 2018), for a period of ten days each quarter, as well as for an additional period of 30 days in an election year, citizens, groups of citizens, companies, NGOs, religious trusts, or any body incorporated in India can buy electoral bonds anonymously from designated State Bank of India (SBI) branches to donate to political parties. Electoral bonds are interest-free and can be purchased in multiples of Rs. 1,000, Rs. 10,000, Rs. 1 lakh, Rs. 10 lakh or Rs. 1 crore. Bonds must be encashed by political parties in their Election Commission-verified bank accounts within 15 days. Importantly, bonds can only be bought using cheques or digital payments from KYC-compliant bank accounts. While SBI will have information on who is donating how much to which political party, the political party and the public will not have access to this information.

Certain provisions of this policy, at face value, ensure a cleaner process of donating to political parties. The use of banking methods rather than cash, for instance, reduces the risk of money laundering and encourages donors to utilise official channels.

The primary point of contention here is the anonymity of the donor. Proponents of electoral bonds argue that this encourages individuals and organizations to use bonds rather than more dubious methods of donation (Chishti 2018; Sethi 2018). The government will not be able to favour certain individuals or organizations since they are unaware of the identity of their donors.

On the other hand, opponents of electoral bonds argue that this policy actively erodes transparency (Sethi 2018). Keeping the payee anonymous, some argue, is a deliberate effort to obscure the electoral process and keep voters in the dark about who donates money to whom (Sethi 2018; Venkataramakrishnan 2018). Anonymity and ‘clean’ money have been presented as increased transparency. However when approached from the voter’s point of view, she has as much (if not less) knowledge as she did before about political party funds. Anonymous cash donations have simply been replaced by another form of anonymous donations – albeit through more formal channels – raising the question of where exactly, if at all, the increased transparency lies.

One can raise the counter question, that of why the voter needs to know the source of party funds at all. This is simply because the voter has the right to make an informed choice while voting (Election Commission of India 2006). Understanding where a party receives its monies from and what the implications of this might be are a vital part of making this choice. It is also fundamental to ensuring transparency. Besides, insisting that the identity of the donor will remain unknown even to the party seems improbable at best, given that it is impossible to prohibit donors and parties from communicating with each other altogether. If this policy ensures that only the public is kept in the dark, it is fair to ask whether electoral bonds realistically increase transparency.

Impact and implications of electoral bonds

According to an RTI application, in January and March of this year, electoral bonds worth Rs. 1716.05 crore were sold (Scroll 2019). Granted that this is an election year and we can expect sales to be higher, but the flip side of that argument is that since it is an election year, public knowledge of party funding is more vital now than at any other time. Lobbies or interest groups might try to influence policy and legislature, but it is unhealthy for the voter and the democracy at large to be unaware of where the party’s loyalties lie. Anonymity also runs the risk of pushing the state-corporate nexus further into the shadows. Limiting transparency to mean reducing the influx of black money and protecting the identity of the donor begs the question: does the donor matter more than the individual voter to Indian political parties?

Conclusion

This policy offers a solution to the cash donation problem, but fixing only one aspect while shrouding the rest of the process in greater opacity does not bode well for India’s democracy (Achary 2019). For all intents and purposes, electoral bonds fail to provide the voter with meaningful information that aids her in making more informed voting choices. This seriously challenges the transparency claim made by the policy. Fundamentally, if political parties do not work for the people, how can the governments they form serve the people?

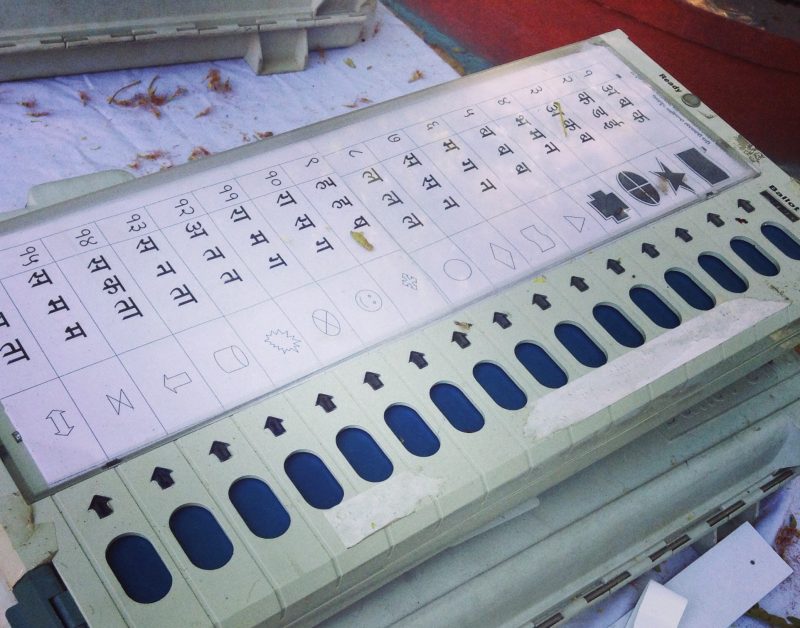

Image: AbhiSuryawanshi via Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0]

References

Achary, P D T. (2019, April 03). Bonds of secrecy. Retrieved 8 April 2019, from Indian Express: https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/lok-sabha-elections-electoral-bonds-of-secrecy-political-parties-5655406/

Chishti, Seema. (2018, January 08). Electoral Bonds: How they’ll work, how ‘transparent’ they’ll really be. Retrieved 8 April 2019, from Indian Express: https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/electoral-bonds-election-funding-arun-jaitley-party-finances-political-donations-india-5015438/

Election Commission of India. (2006). A Guide for Voters. New Delhi: Government of India

Government of India. (2018, January 02). The Government of India Notifies the Scheme of Electoral Bonds to Cleanse the System of Political Funding in the Country; Electoral Bond would be a Bearer Instrument in the Nature of a Promissory Note and an Interest Free Banking Instrument; Bond(s) would be issued/purchased for any Value, in Multiples of Rs.1,000, Rs.10,000, Rs.1,00,000, Rs.10,00,000 and Rs.1,00,00,000 from the Specified Branches of the State Bank of India (SBI). New Delhi: Press Information Bureau (Release ID: 1515123). Retrieved 8 April 2019, from Press Information Bureau: http://pib.nic.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1515123

Jaitley, Arun (2017). Budget Speech, 2017-18. Ministry of Finance, New Delhi: Government of India.

Meghnad S. (2017, February 06). Why Jaitley’s Political Funding Reforms Won’t End Anonymous Donations. Retrieved 8 April 2019, from The Wire: https://thewire.in/politics/jaitley-political-funding-reforms-budget-anonymous-donations

Rajagopal, Krishnadas. (2019, April 12). Give Info to ECI on Each Donor, Each Electoral Bond in Sealed Covers: SC Orders Political Parties. Retrieved 15 April 2019, from The Hindu: https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/give-info-to-eci-on-each-donor-each-electoral-bond-in-sealed-covers-sc-orders-political-parties/article26815706.ece

Scroll. (2019, April 01). Electoral bonds worth Rs 1,716 crore already sold this year, Rs 1,057 crore in 2018: RTI. Retrieved 8 April 2019, from Scroll: https://scroll.in/article/874076/as-electoral-bonds-go-on-sale-again-the-lack-of-transparency-may-be-the-source-of-their-popularity

Sethi, Nitin. (2018, January 04). The Fine Print: Groups of Individuals, NGOs can Buy Electoral Bonds without Public Disclosure. Retrieved 8 April 2019, from Scroll: https://scroll.in/article/863782/the-fine-print-groups-of-individuals-ngos-can-buy-electoral-bonds-without-public-disclosure

Stevens, Harry and Sethi, Aman and. (2017, April 14). Electoral Trusts: How some of India’s Biggest Companies Route Money to Political Parties. Retrieved 9 April 2019, from Hindustan Times: https://www.hindustantimes.com/interactives/electoral-trusts-explained/

The Wire. (2018, January 07). Arun Jaitley on Why Electoral Bonds are Necessary. Retrieved 8 April 2019, from The Wire: https://thewire.in/politics/arun-jaitley-electoral-bonds-necessary

Venkataramakrishnan, Rohan. (2018, April 02). As electoral bonds go on sale again, their popularity may lie in absence of transparency around them. Retrieved 8 April 2019, from Scroll: https://scroll.in/article/874076/as-electoral-bonds-go-on-sale-again-the-lack-of-transparency-may-be-the-source-of-their-popularity