DISCLAIMER: The information and views set out in this article are those of the author(s); and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Centre for Policy Studies or the Indian Institute of Technology Bombay.

This is Part 1 of a Three-Part Series. Click here for Part 2 (Backward Cities Need Each Other) and here for Part 3 (From Barriers To Compartmentalisation)

When societies break, social scientists get more information about how they work. Just so, when an immediate lockdown of the Indian economy was called by the PM on March 24th, a cascade of misery emerged as poor migrants in shuttered cities started to flee to their homes by any and all means. I argue that this illustrates a kind of internal, economic colonialism within India. And, remote as it may seem at this moment, this crisis might actually give us an opportunity to break this pattern.

This essay is divided into three parts. Part 1 outlines the difference between political and economic colonialism and suggests that India’s internal economic pattern might be described as colonial. Part 2 provides a very brief, thumbnail account of the ideas of Jane Jacobs (1970, 1985), who re-redefined economic development as the process whereby local networks of cities undertake work that is import-replacing. Part 3 suggests that such networks might actually be catalysed in the conditions prevailing under the Covid-19 crisis, namely a fragmentation of inter- and intra-national economic space. Some barriers or compartments are highly functional for import-replacing work to take off, so there might be a way to make a virtue of the crisis-driven necessity of breaking up economic space.

Part 1: Pax Indica

Political vs. Economic Imperialism

What is an empire? The political definition follows sovereignty: who gets to make decisions, people from ‘here’ or ‘invaders’ from somewhere else? The boundaries of ‘here’, the nation, are continually constructed and contested but they are somewhat stable at any given time. India is anomalous in this regard because our nation contains multitudes. Built on imperial foundations, our nationalist conceit was to break the European mould and forge a nation out of an empire unified not by blood and soil but by ideas of freedom, self-reliance, social justice, and mutual respect for different faiths and cultures.

The vastness and diversity of the British Indian Empire meant that any nation emerging from it could not possibly claim any cultural unity; facts dictated that if the entity called India were to be a nation, it had to be a civic one rather than an ethnic one. Notwithstanding the horrors of Partition, turning a multitudinous empire into India was a singular achievement.

Of course, this garb of nationalism conceals many different kinds of injustices and inequalities, chief among them economic. This leads us to another definition of imperialism, one based less on politics than economics. Our political status might read ‘free’, but what of our substantive economic status? We might be free to vote, but we are constrained to sell our labour to the highest bidder in order to survive. If there are insufficient takers for our labour in our district or even our state, such a bidder might well be from somewhere else; we have to move closer to them to earn a livelihood.

But migration by itself does not necessarily index imperial economic relations. Recall that the standard colonial pattern of trade was for manufactured goods to flow from the imperial metropole to the colonial periphery, with primary goods and raw materials flowing the other way. Note also that this was true of formally free nations as well: much of Latin America achieved formal independence in the late nineteenth century only to be economically subjected to what economic historians Gallagher and Robinson (1953) have famously called ‘the imperialism of free trade’. An expanding British economy needed markets, raw materials, and destinations for profitable investment. If formal political control was required to ensure these, so be it; but formal political control was secondary to economic penetration. While political control ran the spectrum from formal to informal, what was operative was the relationship of economic inequality, “colonialism” by another name.

Indeed, so stable was this Latin American colonial pattern that it lasted well into the post World War II period, giving rise to the ideas of the dependency school and support for import substitution industrialisation (ISI), a policy package that India took up along with most post-colonial nations who similarly suffered from impoverishing economic patterns. The prevailing empirical pattern, documented in the late 1940s by UN economists Prebisch and Singer, was that the terms of trade between primary and secondary commodities would always move against the former thereby steadily immiserating those nations in the colonial position (Toye & Toye, 2003).

Our Own Empire

So we have economic imperialism – as expressed in unequal and immiserating spacio-economic patterns – and political imperialism in terms of formal decision making control. Within India, we do not naturally have formal internal imperialism even though centre-state relations have at various times been framed like that by certain actors in certain states. We have always been concerned about ‘regional inequalities’, the terms of trade between rural and urban India, but this concern has always been cast in the planning terms of resource transfers rather than economic dynamics. What we do have is a highly centralised polity thanks to the framer’s fear of ‘fissiparous tendencies’. While the classic informal empire entailed political as well as economic influence, Indian ‘imperial’ politics are displaced through centre-state relations rather than those of core-periphery. The context of a nation state results in a disjuncture between internal imperial economic relations and federal political relations.

What of our internal economic pattern? If a stable spatial pattern emerges whereby primary goods from one set of states are shipped to another set of states; while purchases of manufactured goods indicate a similar, inverse pattern, then an economically imperial arrangement can be said to have emerged. Such a pattern has indeed emerged in India as the current migrant crisis brutally reveals.

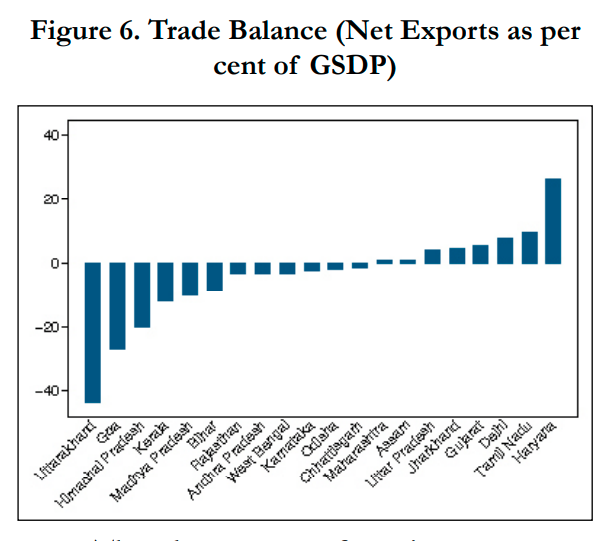

Let us look at some stylized evidence, drawn mainly from the government’s Economic Survey 2016-17 (MoF GoI, 2016). With national GST data available for the first time, the Economic Survey was able to capture our internal balance of trade. There were few surprises.

SOURCE: https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/budget2017-2018/es2016-17/echap11.pdf

To get a sense of the scale, about 54% of India’s GDP is represented by interstate trade, low in comparison to the US or China (around 75%), but still substantial. We can see that the manufacturing-heavy states of Tamilnadu, Gujarat and Maharashtra are net exporters whereas the poorer states were net importers (Goa is an outlier because GST data does not capture trade inside one firm, ie from branches of the same firm in different states). As the Survey observes, UP’s export surplus numbers are driven mainly by Noida; likewise Haryana’s numbers reflect the productivity of Gurgaon: note it is city regions that are the economically salient geographies rather than the political entities called ‘states’.

We know that manufacturing drives internal trade imbalances, as the Survey has regressed the share of manufacturing in a state’s GDP against its trade volumes and found them to be highly correlated.

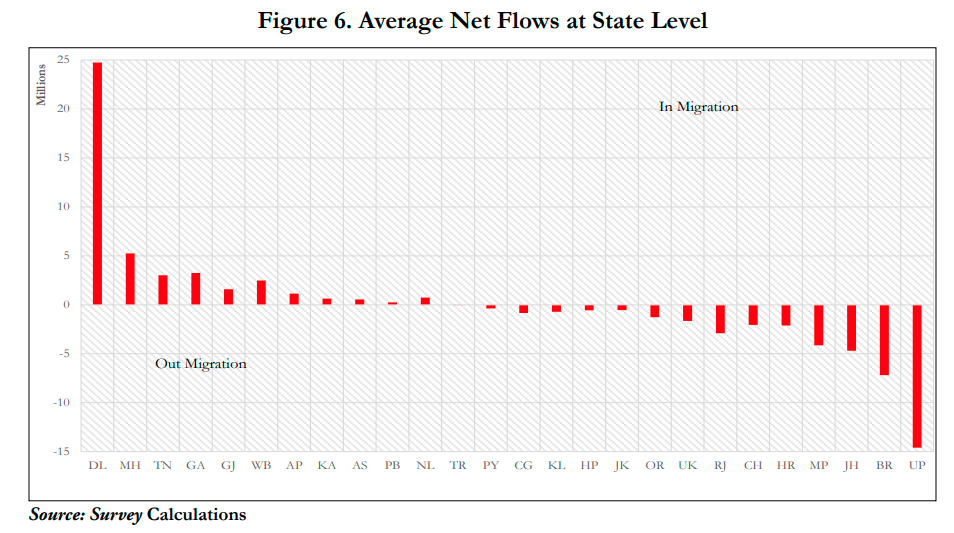

Let us set this balance of internal trade alongside the migration balance, also taken from the Economic Survey:

SOURCE: https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/budget2017-2018/es2016-17/echap12.pdf

Again, no huge surprises here with the city regions of Delhi, Mumbai and the manufacturing states of Tamilnadu and Gujarat (and presumably their respective city regions) taking in the bulk of migrants, and UP, Bihar, Jharkhand and MP sending out the most. Using railway passenger data to calculate net migration, the Economic Survey notes that since 2011, annual net internal migration has been close to 9 million people per year.

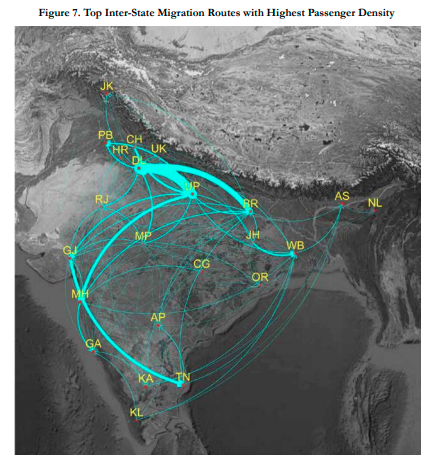

SOURCE: https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/budget2017-2018/es2016-17/echap12.pdf

The traditional colonial trade in raw materials is hard to capture in this data, but in any case we know that the market for agricultural products in India is still quite local thanks to the dominance of Agriculture Produce Market Committees (APMCs) in the states; agricultural marketing is a state subject in India. (In fact, despite some efforts we have so far avoided (Khanal, 2016) ‘globalisation in one country’ on agriculture, something we argue is to be celebrated but repurposed). Yet the migration flows indicate a deeper ‘trade’ in primary goods, that of ‘human capital’ itself.

What poorer states are exporting, in other words, is their most precious natural resource, their people. According to the 2011 Census (GoI, 2011), 455 million Indians are migrants, almost 40% of the population. If migrants were a state, they would be the largest by some orders of magnitude (UP is home to 200 million people). And these are not new flows: these migration patterns have been stable for over a century (Tumbe, 2012).

So here is India’s internal colonial economic pattern: one set of states export manufactured goods and “import people” while another set consume those manufactures and pay for them by “exporting” their people who then remit money back home to purchase advanced-state finished goods. To be sure, many of these flows of people are not one-way traffic but circular as people maintain close links to their villages especially during harvest seasons. But this circulation of people and money only emphasises a colonial division of labour: people circulate between roles that are recognisably colonial in their spatial organisation. As for money, Singh and Singh (2019) note that domestic remittances stacked up to approximately Rs 200 billion for 2007-08 and represented significant shares of state GDP in some cases: Bihar’s remittances amount to 3.66% of state GDP.

Our internal colonial economies have been made too stagnant to absorb their people in the production of manufactured goods, so they import these goods from richer states while exporting natural resources exactly in the pattern of traditional colonial economies. These economies are kept this way by the dynamic of economic colonialism, that is defined by trade between unequals.

Our nationalist movement was built on the idea of a drain of wealth from India to Britain. Our founding fathers and mothers understood both analytically and from brute experience that British colonialism kept us poor by holding our markets open (free trade!) for the products of Lancashire, thus preventing the emergence of domestic industry. Our own experience with ‘deindustrialisation’ at the hands of empire should alert us to the dangers of trading between areas with radically different economic capacities.

Backward-nation industries can no more compete with those of advanced nations than a 9-year-old cricketer can compete with a 16-year-old, yet that was and remains the common sense of free trade and ‘liberalisation’ (I use the term “backward” merely to describe economic conditions). Only freedom from British rule would enable a newly-sovereign Indian state to protect its infant industries and grow itself out of wretched poverty. Not for nothing does the symbol on our flag represent self-reliance.

Of course, the promise of our economic nationalism failed substantially as we were politically unable to discipline over-protected infant industries. They grew into today’s oligarchs while the bulk of the nation remained poor and subject to kafkaesque state controls, a combination that drove many in the middle classes into a somewhat romantic embrace of the philosophy of liberalism. Yet this romance is doomed to tragedy since it means turning our collective backs to a stark historical fact. No nation has ever developed without some measure of protection: not the UK, not the USA, not Japan, Korea, China…none (Chang, 2002). It seems we are condemned to get protection right since there is no other pathway out of poverty. But in an unevenly-developed, continent-sized nation, this means both internal and external protection. This is where this crisis might turn out to be an opportunity.

‘Development’ here means more than becoming rich through commerce of any kind. As we explore in the next section, ‘development’ very much depends on what kind of commerce a region engages in; colonial trade did after all make certain sections of Indian society extremely wealthy even while it failed to develop most of the economy.

It is in this sense that the Indian ‘liberalisation’ of the 1990s overcorrected; we were again thrown to the wind of free trade before we could properly compete. Contrary to free trade nostrums, three decades of liberalisation has not disciplined Indian productivity and brought it to global levels of competitiveness; we can still barely produce a mobile phone domestically even while any growth we have enjoyed has not created sufficient jobs.

From the point of view of liberalism, this is thanks to incomplete reforms rather than any deep flaw in the doctrine. Yet while India’s external trade might not be entirely open (certainly not to the liking of free traders) we still have a trade/GDP ratio of almost 50%, which is substantial (World Bank). And whatever our external barriers, our internal barriers are obviously lower.

Thus, from the point of view of advanced manufacturing states, their industries enjoy more protection from global competition than they do from domestic competition. Backward states, on the other hand, enjoy relatively little protection from the manufacturing of advanced states: there is substantially more “free trade” internal to India than between India and the rest of the world. Backward states therefore find themselves in the ‘colonial’ position, related to advanced states as colonial India was to imperial Britain.

Acknowledgements: My thanks to Siva Arumugam, Srinath Raghavan, and Rahul Srivastava for helpful comments. All errors remain mine.

References

Chang, H. J. (2002). Kicking away the ladder: development strategy in historical perspective. London, England: Anthem Press.

Ellerman, D. (2004, December). Jane Jacobs on development. Oxford Development Studies, 32(4), 507-521.

Gallagher, J., & Robinson, R. (1953). The imperialism of free trade. The Economic History Review, 6(1), 1-15.

Government of India, Ministry of Finance. (2016). Economic survey.

Jacobs, J. (1970). The Economy of Cities. New York, USA: Vintage.

Jacobs, J. (1985). Cities and the wealth of nations: Principles of economic life. New York, USA: Vintage.

Khanal, S. (2016, March). Determinants of inter-State agricultural trade in India (No. 155). ARTNeT Working Paper Series.

Parpiani, Maansi (2020, April 4). Fighting Fires: Migrant Workers in Mumbai. Economic and Political Weekly, 55 (14), 13-15.

Science Direct. Dependency Theory. Retrieved 23 April 2020 from Science Direct: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/economics-econometrics-and-finance/dependency-theory

Singh, B. D. R. and Rajni Singh, (2019). Domestic Remittances, in Rajan, S. I., & Sumeetha, M. (Eds.). Handbook of Internal Migration in India. New York, Sage Publications.

Toye, J.F.J., & Toye, R. (2003). The Origins and Interpretation of the Prebisch-Singer Thesis. History of Political Economy 35(3), 437-467.

Tumbe, C. (2012, October 25). Migration persistence across twentieth century India. Migration and Development, 1(1), 87-112.

Van Leemput, E. (2016, December). A passage to india: Quantifying internal and external barriers to trade. FRB International Finance Discussion Paper, (1185).

World Bank. Retrieved 16 April 2020 from World Bank: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NE.TRD.GNFS.ZS?locations=IN-CN-1W

Image: ILO/J. Urmila 2018 via. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 IGO