DISCLAIMER: The information and views set out in this article are those of the author(s); and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Centre for Policy Studies or the Indian Institute of Technology Bombay.

This article was first published by Hindustan Times; and is reprinted here with permission.

While it may seem like it’s a worthy trade to sacrifice individual privacy to contain the pandemic, it is decisions taken in the eye of the storm that will ripple outwards, creating situations and precedents for future emergencies.

We live in an age marked by one overarching phenomenon — surveillance. Operationalised through electronics and analysed through algorithms, everyday surveillance of the minutiae of our lives has become the defining feature of our times. The data exhaust from our mundane, everyday lives is collected, collated and analysed; and returned to us in many forms such as recommendations on what else we’d like to buy on shopping apps, the manner in which our social media feeds are ordered, and as activists have found out, even government officials showing up at their doorsteps. Much ink has been spilled in describing the many ways in which such surveillance can be harmful, especially in the hands of private corporations and authoritarian regimes.

But, as with everything, the phenomenon of surveillance itself is value neutral. It is neither inherently good or inherently bad. Its harm and benefits are made operational by the manner in which it is deployed. While there are excellent reasons to stop collecting and collating so much data about users; there are some spaces in which surveillance is a vital tool. One of those areas is public health. Surveillance as a tool to study and safeguard from epidemics is a method as old as modern medicine itself. Since the time of Hippocrates, observation and analysis of data has been the cornerstone of modern medicine. Throughout history, attempts at early detection and effective surveillance of diseases have helped not just curb the spread of communicable diseases, but also understand diseases themselves and develop treatment paradigms. Polio is a case in point. The complete eradication of polio in India was a resounding victory for effective surveillance and reporting.

The World Health Organization (WHO), the public health arm of the United Nations (UN) lists integrated disease surveillance as part of its important functions. In such surveillance, countries are required to report any cases of notifiable infectious diseases to WHO. The data thus collected helps analyse the spread and severity of the disease, and to quickly and efficiently put in place protocols to handle the crisis and contain the spread in the case of an epidemic. Disease surveillance, in order to be effective, must be continuous and systematic. This automatically means the continuous collection of data from everywhere.

In comparison to the kind and amount of data that data brokers have about our everyday habits, the amount of viable health data that is available for analysis even in countries such as the United States and Britain is abysmal. Even within the much-vaunted National Health Service (NHS) in the United Kingdom, datasets are sparse and often disconnected. This makes it harder for doctors to trace patients’ histories across regions or find common threads among diseases and treatment protocols within the system.

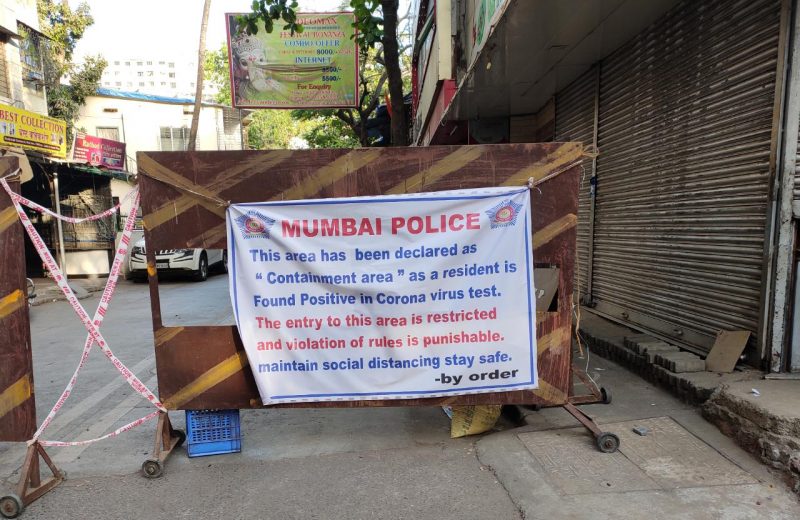

In case of the coronavirus pandemic, finding those who carry the virus and preventing others from coming into contact with them is so far the only effective means of preventing the spread. But here, it is the process of finding that has set off surveillance and privacy alarm bells. Whether it’s European, Israeli and Chinese governments accessing mobile phone location data to ensure that people are obeying lockdown orders or the Karnataka government publishing online the names and contact details of people who have returned from abroad, breaches of individual privacy in these pandemic times are becoming commonplace.

In cases where diseases carry stigma — such as HIV — knowledge of disease history and a breach in anonymity of cases can be particularly harmful. We have already seen this in India with coronavirus cases, where individuals and families face social ostracisation. Several Indians have even taken to ostracising doctors who are working at the frontlines of the fight against the coronavirus.

It is in this context that privacy must be taken into consideration by government agencies while continuing to battle the pandemic. As several commentators have pointed out, measures taken during extreme situations have a sneaky way of becoming business-as-usual, even after the emergency is over. And as we know from several generations of caste discrimination, social ostracisation sticks very easily. One other clear upshot of privacy violations is that a fear of ostracism and mistrust of authorities could prevent people from coming forward to report their symptoms and travel history. With no protocols for data security and preventing personal details of individuals from becoming public; case surveillance in the Internet age can lead to dangerous consequences. The phone numbers and addresses of specific people, for instance, can easily be culled from a public database of people returning home from abroad. Linking this one database to many others can also reveal many other details of individuals, to anyone who comes looking.

In such a situation, while it may seem like it’s a worthy trade to sacrifice individual privacy to contain the pandemic, it is decisions taken in the eye of the storm that will ripple outwards, creating situations and precedents for future emergencies. A pandemic in the age of digital surveillance and big data compounds public vulnerabilities; adding to the looming health and economic crises. This is, therefore, the best time to ask questions about the efficacy of the surveillance in each administrative block — from individual villages and residential complexes to nation-states and WHO itself. What is the information that it is important to know, who absolutely requires to know, how much of it requires dissemination, how can it be effectively collated and reported, and how may we protect the individuals who are already dealing with fear and uncertainty are the important questions to ask.

Image: Vidya Subramanian